Getting to the source: Understanding metadata removal on social media

Scrubbed. Sanitized. Stripped. Laundered. These words are frequently used in digital forensics to describe metadata missing from media files posted to social media sites or transmitted through messaging platforms. Digital forensic examiners and investigators have long voiced concerns about the difficulty in gathering actionable information from media posted online due to this lack of metadata. A common misconception is that this metadata is deliberately removed by platforms before a file is posted. However, this is not the case.

A clearer understanding of what happens to this metadata reveals that websites and platforms do not delete specific metadata values when posting or transmitting media files. Instead of removing metadata values, these video files that lack the original metadata are, in fact, completely new files created by the website or platform. Because these are entirely new files, they may share some of the same attributes as the original file, but those attributes—as well as all other aspects of the file—are newly encoded by the platform, not simply retained from the original file. This is a generative process, where new files are built, rather than an editorial process that selectively removes any data.

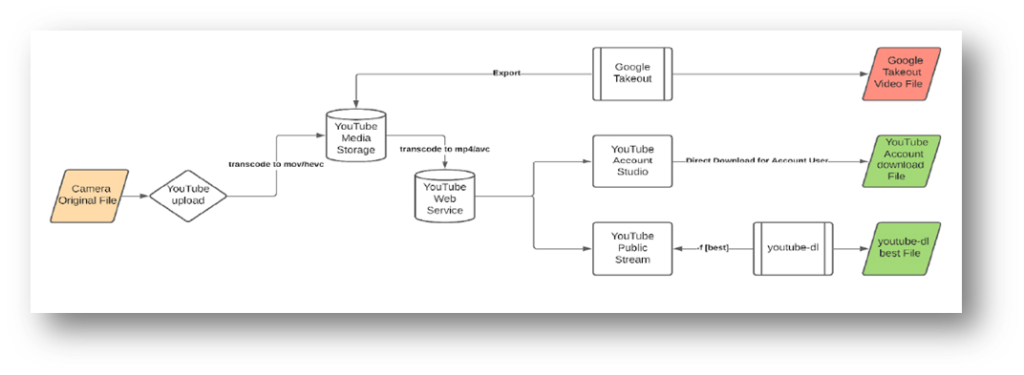

As a simple example, consider a video uploaded to YouTube. Once a file reaches YouTube’s servers, it is transcoded to a new HEVC video encoded into a MOV container by YouTube’s media encoders. This means that after the original video is uploaded to YouTube, a completely new file is immediately created. At this point, YouTube is taking the original pixel values from the submitted video and creating new values. Those pixels will look very similar to the original video, but they are not exact duplicates. YouTube will also create this new file in the MOV format, creating an entirely new set of metadata for this file. Certain YouTube media encoders may generate some of the same metadata values as the original file, however others may generate entirely new values. New metadata tags may also be added (e.g., “ISO Media file produced by Google Inc…”), while other metadata tags may be excluded (e.g., GPS coordinates, software versions). This newly created video file is then stored by YouTube, while the originally submitted file is no longer needed and is discarded.

This newly created video file is stored within the YouTube environment and used as the source for any future derivatives created for public consumption. For example, yet another file is generated from this new source file for access by the public on YouTube’s streaming platform. This second new file is optimized for YouTube streaming and is reencoded into AVC at a lower resolution than the HEVC file, then encoded into an MP4 container instead of an MOV container. If we think about the enormous resources required to effectively store and stream millions of hours of video footage, we see the necessity of creating these new normalized and optimized videos. From the original video, YouTube has generated two new files for use within the YouTube ecosystem, and the file which was originally submitted has been discarded.

When downloading YouTube videos using third party tools such as yt-dlp (or other tools powered by yt-dlp), we are gaining access to the second video discussed above, i.e., the one encoded as AVC in an MP4 container and optimized for streaming online. This downloaded file is now the third incarnation of the video which was originally submitted, and the second time it has been encoded into a new container with new metadata.

YouTube is only one example of how platforms handle media files. Although the exact process will vary on other platforms such as Instagram, TikTok, and WhatsApp, it still involves the creation of new media files, not the retention of a submitted file with deleted data.

As is now clear, the lack of metadata in posted or transmitted media is a result of this data not being created when those media files are optimized for storage, streaming, and/or transmission. These new media files are not simply the original files minus metadata. They have not been “scrubbed” during this process. These are completely new files, and the metadata values which examiners and investigators are looking for were never created. Although the original metadata from the submitted video file is no longer present in these new files, it is not accurate to say that it has been removed. This understanding is important not only to describe why metadata is or is not present, but to understand which files to acquire and the best way to examine them.

To address the challenges of re-encoded media files, investigators must focus on obtaining original files whenever possible. By using advanced forensic tools to analyze files and any available metadata, investigators can validate the authenticity of a video file. Additionally, hashing techniques and pixel-level analysis can help identify valuable evidence. Understanding how solutions such as Magnet Verify identify media allows investigators to make informed decisions and assess the integrity and reliability of digital evidence, ensuring that the findings can be confidently used in legal proceedings or investigative actions.

For more information, contact sales@magnetforensics.com.