Forensic Analysis of Windows Shellbags

This is the fifth and final blog post in a series about recovering Business Applications & OS Artifacts for your digital forensics investigations.

What are Shellbags?

While shellbags have been available since Windows XP, they have only recently become a popular artifact as examiners are beginning to realize their potential value to an investigation. Shellbags are a set of registry keys that store information about the view settings and preferences of folders as they are viewed in Windows Explorer. These settings include details such as icon size, position, view mode (e.g., list, details, tiles), and window size. ShellBags record the state of folder views to provide a consistent and personalized user experience each time a folder is accessed. They effectively remember how a user last viewed a particular folder, even after the folder is closed and reopened, ensuring that the same view settings are applied. This includes local drives, network shares and removable devices.

Why are Shellbags important to digital forensics investigations?

One might ask why the position, view, or size of a given folder window is important to forensic investigators. While these properties might not be overly valuable to an investigation, Windows creates a number of additional artifacts when storing these properties in the registry, giving the investigator great insight into the folder, browsing history of a suspect, as well as details for any folder that might no longer exist on a system (due to deletion, or being located on a removable device).

Changes to Shellbags by Windows version

In Windows XP, Shellbags were located in the NTUSER.DAT (\users\<username>\NTUSER.DAT). Specifically within the NTUSER.DAT hive at:

HKEY_CURRENT_USER\Software\Microsoft\Windows\ShellNoRoam\BagMRU

HKEY_CURRENT_USER\Software\Microsoft\Windows\ShellNoRoam\Bags

For Windows Vista, additional shellbag information was also located within the hive UsrClass.dat (C:\Users\<Username>\AppData\Local\Microsoft\Windows\UsrClass.dat).

HKEY_CURRENT_USER\Software\Classes\Local Settings\Software\Microsoft\Windows\Shell\Bags

NTUSER.DAT:

- HKEY_CURRENT_USER\Software\Microsoft\Windows\Shell\BagMRU

- HKEY_CURRENT_USER\Software\Microsoft\Windows\Shell\Bags

UsrClass.dat:

- HKEY_CURRENT_USER\Software\Classes\Local Settings\Software\Microsoft\Windows\Shell\BagMRU

- HKEY_CURRENT_USER\Software\Classes\Local Settings\Software\Microsoft\Windows\Shell\Bags

They also made the following changes:

• More detailed metadata is stored, including timestamps for folder creation, last access, and modification times, providing greater forensic value.

• Enhanced tracking of folder views and settings, including special folders and more comprehensive support for network locations and removable devices.

• Expanded types of shell objects and folders tracked by ShellBags, improving the ability to track a wider variety of user interactions with the file system.

For Windows 7, the same registry paths as Windows Vista were maintained. The following changes were made:

• Expanded the types of shell objects and folders tracked by ShellBags, including better support for virtual folders and library views introduced in Windows 7.

• Improved tracking of user preferences for folder views across sessions and reboots.

For Windows 8/8.1, the registry paths had no change. The following changes were made:

• Enhanced support for tracking modern apps and new shell features.

• Improved handling of view settings for virtual folders and libraries.

• Greater consistency in the application of user preferences across different devices and network locations.

For Windows 10, the registry paths had no changes. The following changes were made:

• More granular and detailed tracking of user interactions with the file system.

• Enhanced metadata storage, including precise timestamps and detailed folder settings.

• Improved support for Universal Windows Platform (UWP) apps and other modern shell features.

For Windows 11, again the registry path had no changes. The following changes were made:

• Advanced tracking capabilities, including better support for hybrid and cloud-based storage environments.

• Enhanced metadata accuracy, providing more precise information for forensic analysis.

• Improved user experience with more reliable and consistent application of folder view settings.

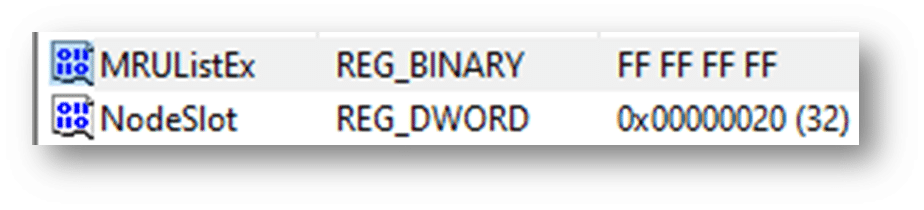

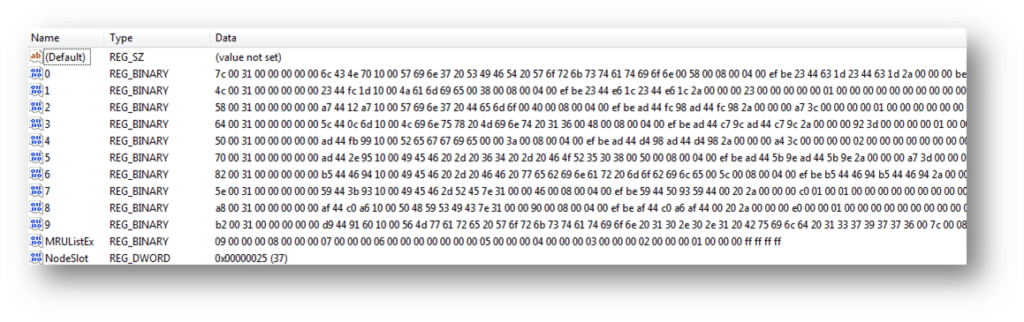

The shellbags are structured in the BagMRU key in a similar format to the hierarchy to which they are accessed through Windows Explorer with each numbered folder representing a parent or child folder of the one previous. Within each of those folders are the MRUListEx, NodeSlot, and NodeSlots keys:

MRUListEx contains a 4-byte value indicating the order in which each child folder under the BagMRU hierarchy was last accessed. For example if a given folder has three child folders labelled 0, 1, and 2 and folder 2 was the most recently accessed, the MRUListEx will list folder 2 first followed by the correct order of access for folders 0 and 1

NodeSlot value corresponds to the Bags key and the particular view setting that is stored there for that folder. Combining the data from both locations, investigators are able to piece together a number of details around a given folder and how it was viewed by the user

NodeSlots is only found in the root BagMRU subkey and gets updated whenever a new shellbag is created

Below is an output from the Windows Registry Editor showing shellbag data for a particular folder as well as a number of additional folders stored under the user’s mounted E volume:

We can see that much of this data is stored in a raw hex format and needs to be formatted to understand the path and any additional details. You will need to collect data from each value in the hierarchy to piece together the path of the folder and then use data found in the Bags key to find additional details on the icons, position, and timestamp details.

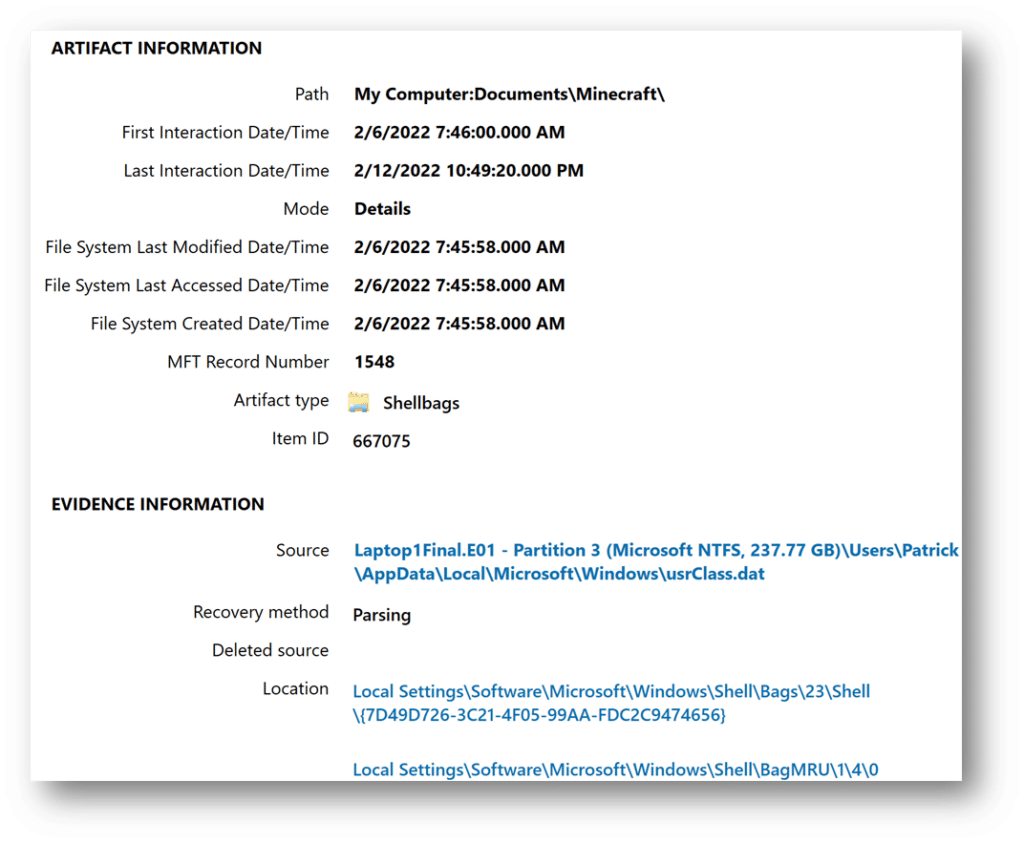

Making Shellbag analysis easier with Magnet Axiom

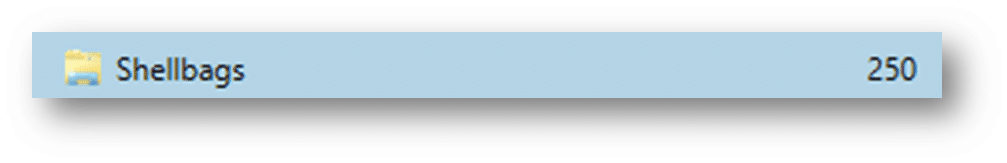

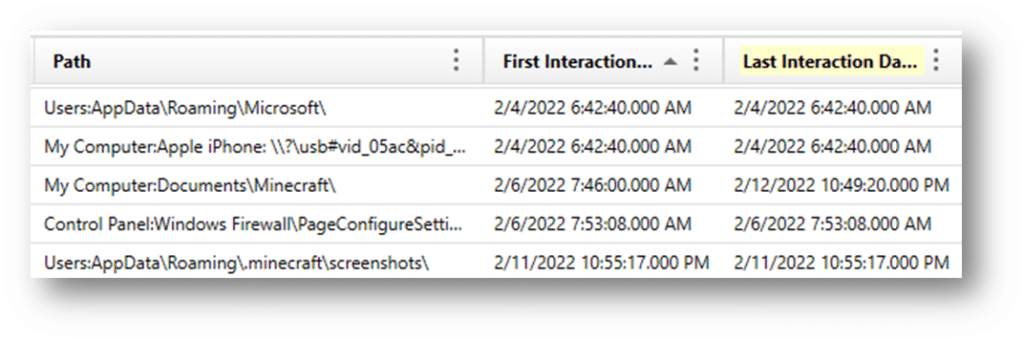

Axiom parses the above details from the NTUSER.dat and UsrClass.dat hives and organize the results into an easy to read and interpret format for investigators. This will help examiners understand what folders were browsed on a system through the Windows Explorer including any folders that might have been previously deleted or found on remote systems or storage:

Of note, you see the original path, the master file table record number, and key timestamps. These timestamps potentially allow investigators to find out the last time a particular folder was viewed. However, when examining the timestamp data, investigators should be conscious of the potential challenges:

- Incomplete Data

• ShellBags only track folders that have been accessed through Windows Explorer, not folders accessed through command-line interfaces, third-party file managers, or automated processes. This can result in an incomplete picture of user activity, as not all folder accesses are recorded. - Data Volatility

• ShellBag data can be easily modified or deleted by users or system processes, either intentionally or unintentionally. Regular system cleanups or the use of privacy tools can also purge this data. - Lack of File-Level Detail

• ShellBags provide information about folder access and view settings but do not track individual file interactions within those folders. - Overwriting of Data

• Windows may overwrite ShellBag entries over time, especially if the number of tracked folders exceeds the system’s capacity to store ShellBag data. - User and System Artifacts Confusion

• Distinguishing between artifacts created by the user and those created by the system or automated processes can be challenging. - Correlation with Other Artifacts

• Relying solely on ShellBags without correlating with other forensic artifacts can result in incomplete or biased conclusions. To form a comprehensive and accurate understanding of user activity, ShellBags data should be corroborated with other sources of evidence such as file system metadata, event logs, prefetch files, and internet history.

Adding shellbags to your analysis will help build a timeline of events, as a user might have traversed through a system going from folder to folder. It may also help refute claims that a suspect might not have known certain files or pictures were present on a system. While proper shellbag analysis can be challenging, the data included in the artifacts can be vital to investigations to determine what a user was doing on a system during a given incident.